Jersey, we’re an Island of cavemen and Vikings, of pirates and of Kings, an Island which wears its vibrant history with pride. We’re a population that’s connected to the sea, and by the sea, the force that shaped our beautiful landscape. Our history is influenced by our very location. Jersey has been invaded and fought over many times through history by those wishing to claim our beautiful shores as their own. Our past is woven into the fabric of time and folklore, the legacy of our ancestors puts Jersey on the pages of history books, their stories echoing through the ages, and into the very customs and traditions of Islanders today.

Cavemen and Vikings

Jersey was a centre of Neolithic activity. 250,000 years ago (50,000 BC) the first Jerseymen and women, nomadic Palaeolithic cave-hunters used our cliffs and caves for hunting Mammoth and Woolly Rhinoceroses.

By 4000 BC our Neolithic ancestors had built communities and settlements turning Jersey into their permanent home. Evidence still stands today, across the Island, of ritual burial chambers such as the Dolmens and La Hougue Bie, and artefacts often unearthed by farmers ploughing their fields.

The Island is also home to the largest European discovery of Iron Age Celtic and Roman coins. The hoard is believed to have belonged to a Curiosolitae tribe fleeing Julius Caesar’s armies around 50 to 60 BC.

Jumping forward in time to 800 AD the Island was plundered by Vikings, but it is believed by some to have gained its name as a result (Jèrri).

Gaining Our Independence

For 300 years, until 1204, Jersey was ruled by Normandy, until the Island swore its allegiance to King John of England.

King Philip II Augustus of France conquered the Normandy territory from King John of England in the Battle of Rouen. The French victory saw the loss of English control over continental Normandy for the first time since William the Conqueror in 1066. However, despite the Island’s ties to France, Jersey was persuaded by King John to swear allegiance to him, no doubt in part because of the support he received from the Norman Knight Pierre de Préaux, who was at the time the Governor of the Channel Islands, and the promises the English King made to Islanders.

Among the promises King John granted Islanders was the right to be governed by their own laws and to be exempt from English tax. He also had the Island select 12 men to act as Jurats to sit with the Bailiff, which became the Jersey Royal Court. King John appointed a Warden who later became the Lieutenant Governor, who was responsible for organising the defence of the Island. The existing Norman customs and laws were allowed to continue, with the only exception being that the head of the legal system was to be the English Monarch rather than the Duke of Normandy.

The Constitutions of King John began the special relationship the Island still has with the English crown and founded modern self-government, and the constitutional position that Jersey enjoys today.

The Beginning of International Trade

Although archaeological evidence shows Jersey was a strategic location along the Brittany to southern England trading route dating back as far as Neolithic times, it wasn’t until the 1500s-1600s that the importance of the Island internationally was truly recognised for its agriculture, milling, fishing, shipbuilding and production of woollen goods. These industries laid the foundations of Jersey’s prosperity.

During the 1500s, because Jersey’s production of woollen knitwear reached such a large scale that it began to threaten the Island’s ability to produce its own food, restrictions were imposed on who could knit and when! However, because England was then at war with much of Europe, Jersey’s woollen trade continued, this trade giving birth to the term ‘Jersey’, replacing the word ‘sweater.’ This highlights the importance the trade had internationally.

This era (1500s) and into the 1600s also saw the development of the Island’s fishing fleet with local fishermen being involved in the Newfoundland cod fisheries. Boats left the Island in February or March, often not returning until September or October, leading to the establishment of colonies of Jersey people in Newfoundland and the building of what are now termed ‘Cod Houses’ – houses built in a Jersey ‘style’ and funded by the large incomes being generated through the fishing trade.

Towards the end of the 17th century, Jersey strengthened its links with the Americas with many Islanders emigrating to New England and northeast Canada to establish businesses in the Newfoundland and Gaspé fisheries. It was these sailors who were recognised globally as belonging to the first rank of seagoing men, and to whom Jersey owes its place among the discoverers of the New World.

Today the Island is still a centre of trade, known as an international offshore business centre, and recognised for its achievements in the finance industry winning accolades such as Top Offshore Finance Centre.

The Island’s agricultural industry has also reached international recognition through the production of Jersey Royal new potatoes and through the globally recognised and revered Jersey cow as well as the dairy product exports from the local herd to places as far afield as Japan and the Middle East.

The New Jersey Connection

During the English Civil War (1642 to 1651), The Prince of Wales, (later known as King Charles II) visited the Island twice seeking protection during the trial and later execution of his father, King Charles I. On 17th February 1649 in the Jersey’s Royal Square, Charles was declared King for the first time in the British Isles.

In thanks and recognition for the refuge and protection he received during his exile, King Charles II gifted the then Bailiff and Governor of Jersey, George Carteret, a large sum of land in the then American colony. George Carteret named this land New Jersey, which is now part of the United States of America. Today both cultural and business links still exist between New Jersey and the Island of Jersey.

Pirates and Privateers - The ‘Corsaires’ of Jersey

In legends and folklore passed down through the generations, you can often hear the extraordinary stories of pirates and sailors, and their treasures hidden in the Island’s caves and gullies. Jerseymen once known for their adventurous spirit, expert seamanship and bravery, are amongst those men of the past who were willing to gamble their lives for a possible prize. Eager to go anywhere where ships were to be found, the Jersey pirates and sea merchants ventured across the world in their small craft.

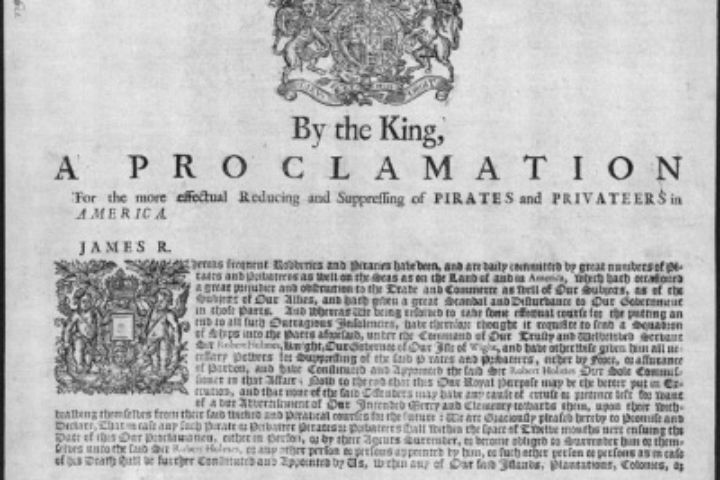

By 1689 privateering was adopted in Jersey as a form of legal piracy, though there was a clear distinction between the two. This entailed the King writing ‘letters of marque’ to those whose property had been seized by an enemy so that owners could recoup their losses.

Eventually however, this was amended so that marques were written to vessel owners authorising them to attack and plunder any of the King’s enemies during war time. Those carrying a marque were called Privateers or Corsaires, with these titles seeming to be a very useful means by which Jersey sailors and merchants could plunder for their own gain. Privateering continued for some time until it was abolished in the Declaration of Paris in 1850.

Many ‘letters of marque’ are still in the possession of the original Jersey families who, to this day, are able to recount stories of their privateer and pirate ancestors.

War and Its Fortresses

Through the decades Jersey has been stuck between the battling English and French, a history which has left its mark on the Island through many fortresses and castles which still stand today. The most remarkable of these are Mont Orgueil Castle, Elizabeth Castle and the array of round towers built by General Sir Henry Seymour Conway in the style of an English Martello tower but with some local adaptations, for example tall tapering walls constructed of local granite with mâchicolations (projecting beak-like structures) high up on the towers and walls.

In 1337 The Hundred Year War began between the French and English, and because of the Island’s proximity to the French mainland Jersey acted as the first line of defence, becoming heavily fortified during this time. The most notable of these fortifications is Mont Orgueil Castle in Gorey, which was intended to serve as a royal fortress and military base.

In 1590 following the excommunication of Elizabeth I by the Pope and the resultant threat imposed to the Island, work began on the construction of Elizabeth Castle in St Aubin’s Bay. The castle was named by the then Governor of Jersey Sir Walter Raleigh.

During The Battle of Jersey (1781) a French invading party captured St Helier and although they were eventually defeated by Major Peirson, a series of round towers were built across the Island to defend against future attacks. Today they stand tall and serve as a stark reminder of the Island’s turbulent past.

The majority of towers and castles are open to the public today serving as museums, and even some as holiday lets for those who want an immersive experience.

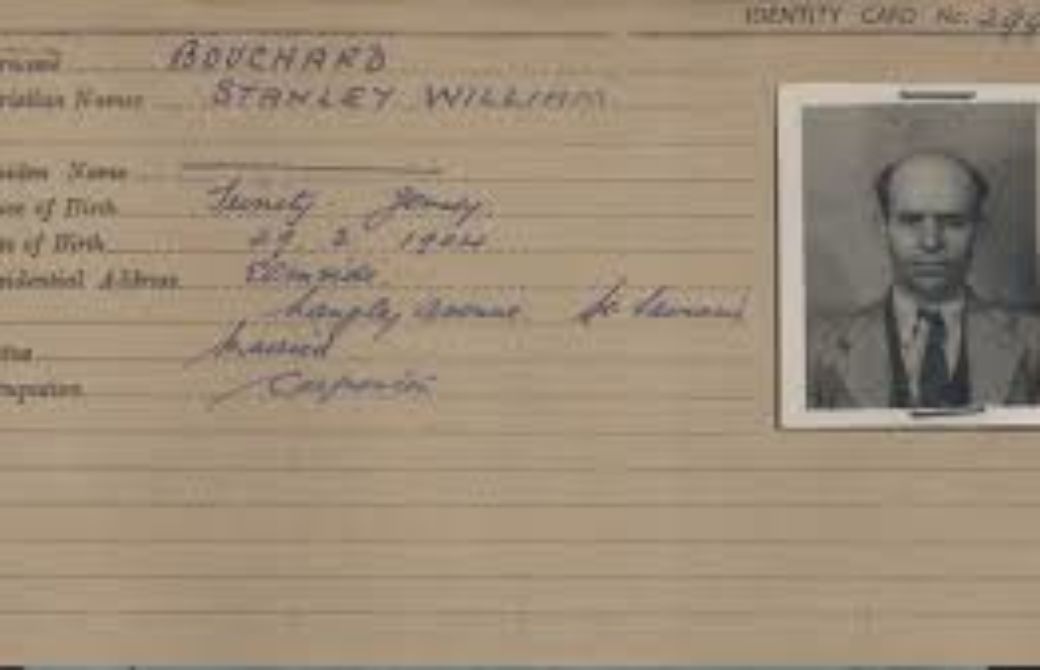

World War II – The Occupation of Jersey

On 30th June 1940 Jersey was invaded and then occupied by German forces.

The Channel Islands were the only part of the British Isles to be occupied, a history still very present on the Island today with the remnants of German bunkers, fortresses and fortified coastal defences, built as part of Nazi Germany’s Atlantic Wall, littered across the Island. After 1,773 days (nearly 5 years later) on 9 May 1945 the Island was liberated, it was one of the last places in Europe to be freed. The liberation is still celebrated today with an annual Bank Holiday and festivities.

There are a number of Islanders still living on the Island today who remember the invasion and what life was like during that time. A number of monuments, signs and museums have also been dedicated to this very difficult time in the Island’s history.

Jèrriais – Our Traditional Language

Jèrriais is our traditional language, a variety of Norman French unique to Jersey, with a rich history and literature. Descended, like French and other related languages, from Latin, it has been marked by the settlement of Vikings who left the influence of their Norse language. Jèrriais has also borrowed words over the centuries from French, from Breton, and increasingly from English.

During the Occupation 1940-1945, Jèrriais was important as a language of resistance, as Jersey people could speak and write without being understood by the Germans. However, with the evacuation of many families to the UK and men going off to war before the Germans arrived, since 1945 the linguistic situation has changed with rapid decline in the speaking of Jèrriais.

According to the latest statistics, 18% of the population claim to be able to speak at least some Jèrriais and 33% claim to be able to understand at least some spoken Jèrriais, but no more than 1% are classed as fluent speakers. Despite its decline Jèrriais is a living language and efforts are being made to keep it alive. Jèrriais has had official status as one of Jersey’s official languages since 2019. Examples of Jèrriais in place names, branding and bilingual signage can be seen in everyday usage, and individual words borrowed into Jersey English may be heard in conversation by people who do not consider themselves Jèrriais speakers.

Jèrriais should not be confused with Jersey Legal French, the variety of French used for some official purposes in Jersey for example laws, documents, administrative titles and functions.

Some of Jersey’s road names and family names reflect this rich history with some being distinctively Jèrriais, and others French.

If you would like to find out more about Jersey please see Why Jersey. To talk to a member of the team use the button below.

Strategically positioned between the UK and Europe, Jersey opens up a world of connections.

- Enviable quality of life and work-life balance

- Highly regarded and well-regulated international jurisdiction

- Safe, secure community lifestyle

- Low personal and business taxes